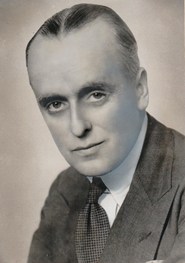

Eric Coates

Eric Francis Harrison Coates[n 1] (27 August 1886 – 21 December 1957) was an English composer of light music and, early in his career, a leading violist.

Coates was born into a musical family, but, despite his wishes and obvious talent, his parents only reluctantly allowed him to pursue a musical career. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music under Frederick Corder (composition) and Lionel Tertis (viola), and played in string quartets and theatre pit bands, before joining symphony orchestras conducted by Thomas Beecham and Henry Wood. Coates's experience as a player added to the rigorous training he had received at the academy and contributed to his skill as a composer.

While still working as a violist, Coates composed songs and other light musical works. In 1919 he gave up the viola permanently and from then until his death he made his living as a composer and occasional conductor. His prolific output includes the London Suite (1932), of which the well-known "Knightsbridge March" is the concluding section; the waltz "By the Sleepy Lagoon" (1930); and "The Dam Busters March" (1954). His early compositions were influenced by the music of Arthur Sullivan and Edward German, but Coates's style evolved in step with changes in musical taste, and his later works incorporate elements derived from jazz and dance-band music. His output consists almost wholly of orchestral music and songs. With the exception of one unsuccessful short ballet, he never wrote for the theatre, and only occasionally for the cinema.

Life and career

[edit]Early years

[edit]Coates was born in Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire, the only son, and youngest of five children, of William Harrison Coates (1851–1935), a medical general practitioner, and his wife, Mary Jane Gwyn, née Blower (1850–1928).[2] It was a musical household: Dr Coates was a capable amateur flautist and singer, and his wife was a fine pianist.[3]

As a child, Coates did not go to school, but was educated with his sisters by a governess. His musicality became clear when he was very young, and asked to be taught to play the violin. His first lessons, from age six, were with a local violin teacher, and from thirteen he studied with George Ellenberger, who was once a pupil of Joseph Joachim.[1] Coates also took lessons in harmony and counterpoint from Ralph Horner, lecturer in music at University College Nottingham, who had studied under Ignaz Moscheles and Ernst Richter and was a former conductor for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.[4] At Ellenberger's request, Coates switched to the viola, supposedly for a single performance; he found the deeper sound of the instrument to his liking and changed permanently from violinist to violist.[5] In that capacity he joined a local string orchestra, for which he wrote his first surviving music, the Ballad, op. 2, dedicated to Ellenberger.[6] It was completed on 23 October 1904 and performed later that year at the Albert Hall, Nottingham, with Coates playing in the viola section.[7]

Coates wanted to pursue a career as a professional musician; his parents were not in favour of it, but eventually agreed that he could seek admission to the Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London. They insisted that by the end of his first year there he must have demonstrated that his abilities were equal to a professional career, failing which he was to return to Nottinghamshire and take up a safe and respectable post in a bank. In 1906, aged twenty, Coates auditioned for admission; he was interviewed by the principal, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, who was sufficiently impressed by the applicant's setting of Burns's "A Red, Red Rose" to suggest that Coates should take composition as his principal study, with the viola as subsidiary. Coates was adamant that his first concern was the viola. Mackenzie's enthusiasm did not extend to offering a scholarship, and Dr Coates had to pay the tuition fees for his son's first year, after which a scholarship was granted.[8]

At the RAM Coates studied the viola with Lionel Tertis and composition with Frederick Corder. Coates made it clear to Corder that he was temperamentally drawn to writing music in a light vein rather than symphonies or oratorios. His songs featured in RAM concerts during his years as a student, and although his first press review called his two songs performed in December 1907 "rather obvious",[9] his four Shakespeare settings were praised the following year for the "charm of a sincere melody".[10] and his "Devon to Me" (also 1908) was credited by The Musical Times as "a robust and manly ditty, worthy of publication".[11]

Coates was fortunate in his viola professor. The New York Times called Tertis the first great protagonist of the instrument,[12] and Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians ranks him as the foremost player of the viola.[13] He was also regarded as a great teacher,[14] and under his tutelage Coates developed into a first-rate viola player.[3] While still a student he earned money playing in theatre orchestras in the West End, including the Savoy, where he played for several weeks under François Cellier in a Gilbert and Sullivan season in 1907.[15]

Professional violist and composer: 1908–1919

[edit]

In 1908 Coates's studies at the RAM came to an unexpected end when Tertis had to drop out of a tour of South Africa as a member of the Hambourg Quartet, a leading string ensemble; he arranged for Coates to be invited to fill the vacancy. Coates resigned his scholarship at the academy and joined the tour. At about this time he began to be troubled by pain in his left hand and numbness in his right, which were symptoms of the neuritis that affected him throughout the remaining eleven years of his career as a violist.[16] After working with the Hambourg Quartet, Coates was violist of the Cathie and Walenn quartets.[17]

Alongside his busy playing career, Coates had several early successes as a composer. The soprano Olga Wood, wife of the conductor Henry Wood, sang Coates's "Four Old English Songs" at the Proms in 1909; the music critic of The Times wrote that they were "tuneful, somewhat in the manner of Mr. Edward German", and showed the influence of Arthur Sullivan in the word-setting.[18] The songs were taken up by other prominent singers including Gervase Elwes, Carrie Tubb and Nellie Melba.[19] The composer's many collaborations with the lyricist Frederic Weatherly began with "Stonecracker John" (1909), the first of a succession of highly popular ballads. Wood was the dedicatee of the Miniature Suite, the last movement of which was encored when he conducted its first performance, at the Proms, in October 1911.[3]

In early 1911 Coates met and fell in love with an RAM student, Phyllis (Phyl) Marguerite Black (1894–1982), an aspiring actress, who was studying recitation. His affections were reciprocated but her parents were doubtful of Coates's prospects as a husband and provider. Although he continued to compose, he was concentrating for the time being on playing the viola for his principal income, first with the Beecham Symphony Orchestra, and, from 1910, with Wood's Queen's Hall Orchestra. He played under the batons of composers including Elgar, Delius, Holst, Richard Strauss, Debussy, and virtuoso conductors such as Willem Mengelberg and Arthur Nikisch.[20] This work gave him the necessary financial security to marry Phyllis in February 1913. They had one child, Austin, born in 1922.[3]

Coates was declared medically unfit for military service in the First World War, and continued his musical career. The war brought about a severe reduction in work, and the couple's income received a welcome boost from Phyllis's acting engagements. As her career progressed she appeared with other rising performers including Noël Coward.[21]

In 1919 Coates gave up playing the viola.[n 2] His contract to lead the section in the Queen's Hall orchestra expired and was not renewed. Some sources ascribe this to Coates's wish to pursue a full-time career as a composer;[23] others say that his neuritis affected his playing;[20] Coates himself said that Wood valued reliability more than virtuosity, and had become exasperated by Coates's frequent absences conducting his compositions elsewhere.[26]

Full-time composer: 1920s and 1930s

[edit]Whether or not Wood had lost patience with Coates as a violist, he regarded him well enough as a composer to invite him to conduct the first performance of his suite Summer Days at a Queen's Hall Promenade concert in October 1919, and to engage him for repeat performances of the piece in 1920, 1924 and 1925,[27] and for more of his orchestral works including the suite Joyous Youth (1922) and the premiere of The Three Bears (1926).[28] The latter, one of three of Coates's most substantial works, labelled "Phantasies", was inspired by the children's stories that Phyllis Coates read to their son; the others were The Selfish Giant (1925) and Cinderella (1930).[29]

What Coates's biographer Geoffrey Self describes as "a not-too-onerous contract with his publisher" stipulated an annual output of two orchestral pieces – one of fifteen minutes' duration and one of five – and three ballads.[24] Coates was a founder-member of the Performing Right Society, and was among the first composers whose main income came from broadcasts and recordings, after the demand for sheet music of popular songs declined in the 1920s and 1930s.[24][30]

Between the First and Second world wars, Coates was in demand as a conductor of his own works, appearing in London and seaside resorts such as Bournemouth, Scarborough and Hastings, which then maintained substantial orchestras devoted to light music.[31] But it was in the studio that he made the most impact as a composer-conductor. Beginning in 1923 he made records of his music for Columbia, which attracted a substantial following. Among those who bought his records was Elgar, who made a point of buying all Coates's discs as they came out.[31][32]

Although he and his wife maintained a country house in Sussex, Coates found city life more stimulating, and was more productive when at the family's London flat in Baker Street. The views from there across the roofscapes prompted his London Suite (1933), with its depictions of Covent Garden, Westminster and Knightsbridge.[33] The work transformed Coates's status from moderate prominence to national celebrity when the BBC chose the "Knightsbridge" march from the suite as the signature tune for its new and prodigiously popular radio programme In Town Tonight, which ran from 1933 to 1960.[34]

Another work written at the Baker Street flat that enhanced the composer's fame was By the Sleepy Lagoon (1930), an orchestral piece that made little initial impression, but with an added lyric became a hit song in the US in 1940,[n 3] and in its original instrumental version became familiar in Britain as the title music of the BBC radio series Desert Island Discs which began in 1942 and (in 2023) is still running.[36]

Later years: 1940–1957

[edit]During the early part of the Second World War, Coates composed little until his wife suggested he might write something for the staff at the Red Cross depot where she was a volunteer worker. The result, the march "Calling All Workers" became one of his best known pieces, benefiting from use as another BBC signature tune, this time for the popular series Music While You Work.[3] At the BBC's request he wrote a report on light music on radio, completed in 1943. Some of his findings and recommendations were accepted but, according to a biographical sketch by Tim McDonald, Coates "failed to bring about any significant lessening of the inherent snobbery within the Corporation which tended to take a rather dismissive view of light music".[37]

Coates was a director of the Performing Right Society, which he represented at international conferences after the war in company with William Walton, A. P. Herbert and others.[38] His autobiography, Suite in Four Movements, was published in 1953. The following year one of his last works became one of his best known. A march theme occurred to him, and he wrote it out and scored it with no particular end in view. Within days the producers of a forthcoming film, The Dam Busters, asked Coates's publishers if he would be willing to provide a march for the film. The new piece was incorporated in the soundtrack and was a considerable success. In a 2003 study of the music for war films, Stuart Jeffries commented that the closing credits of The Dam Busters, with the march as a valedictory anthem, would make later composers of such music despair of matching it.[39][n 4]

On 28 November 1957 Coates made one of his final public appearances at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund held at the Savoy Hotel, playing dulcimer in the premiere performance of Malcolm Arnold's Toy Symphony. On 17 December, he suffered a stroke while at the family's Sussex house and died in the Royal West Sussex Hospital, Chichester after four days there, aged 71.[41] He was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium.[42]

Music

[edit]In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Geoffrey Self writes that Coates consistently recognised and accommodated new fashions in music. As contemporary reviewers observed, his early compositions showed the influence of Sullivan and German, but as the 20th century progressed, Coates absorbed and made use of features of the music of Elgar and Richard Strauss.[24] Coates and his wife were keen dancers,[43] and in the 1920s he made use of the new syncopated dance-band styles.[44] The Selfish Giant (1925) and The Three Bears (1926) show this distantly jazz-derived aspect of Coates's music, with chromatic counter-melodies and use of muted brass.[45]

Self sums up the characteristics of Coates's music as "strong melody, foot-tapping rhythm, brilliant counterpoints, and colourful orchestration".[3] Coates derived the effective orchestration of his scores from his rigorous early training, experience in theatre pits of the practicalities of orchestration and arranging, and from hearing the symphony orchestra from the inside as a viola player.[31] In the works of some composers, orchestral viola parts are frequently uninteresting to play,[46] and having had to do so in Beecham's and Wood's orchestra, Coates was determined that his own compositions would have interesting and colourful music for every instrument of the orchestra.[47]

Coates and his music attracted a certain amount of snobbery:[22] The Times characterised his music as "fundamentally commonplace … but well written, easy on the ear and lightly sentimental … superficial but sincere".[17] In its obituary notice, The Manchester Guardian took issue with such a dismissal, and preferred the French attitude of cherishing petits-maîtres for what they were rather than condemning them for what they were not: "better to write second-class masterpieces than fail to be a second Beethoven".[22] One of Coates's most important musical gifts was the ability to write memorable tunes – "a genuine lyrical impulse" as The Manchester Guardian put it. On first meeting him Dame Ethel Smyth said, "You are the man who writes tunes", and asked him how he did it.[48]

Orchestral

[edit]

Coates's orchestral works are the core of his output, and are the best known.[24] He wrote a few works outside his normal genre – a rhapsody for saxophone and orchestra in 1936 and a "symphonic rhapsody" on Richard Rodgers's "With a song in my heart" – his only treatment of music by another composer. The most extended of his orchestral works (at just under 20 minutes in length) is the tone poem The Enchanted Garden (1938), derived from an abortive ballet on the theme of the Seven Dwarfs, originally composed for André Charlot.[49] But in the main his orchestral works fall into categories: suites, phantasies, marches and waltzes, plus a stand-alone overture and other short orchestral items.[24]

Of the thirteen suites, the most often played are the London Suite (1932), London Again (1936) and a later work, The Three Elizabeths (1944), alluding musically first to Elizabeth I, then Elizabeth of Glamis (the then queen consort), and finally the latter's elder daughter, the future Elizabeth II. The suites generally follow a pattern of robust outer movements with a more reflective inner movement.[24] Of the seven stand-alone waltzes, the best known, "By the Sleepy Lagoon" (1930), is described as a "valse-serenade", although over the years it has been rendered as a beguine, a slow waltz and a slow fox-trot.[50]

In his orchestral scores Coates was particular about metronome markings and accents. When conducting his music, he tended to set fairly brisk tempi, and disliked it when other conductors took his works at slower speeds that, to his mind, made them drag.[51]

Songs

[edit]Coates's first published works were the "Four Old English Songs", written while he was still a student at the RAM.[19] By the end of the 20th century his songs had become much less well known than his orchestral music, but when they were written they were an essential and highly popular part of his output. Grove lists 155 songs, beginning with the three Burns settings (1903) that favourably impressed Mackenzie, and ending with "The Scent of Lilac" (1954) to words by Winifred May.[24]

By the mid-1920s the demand for ballads and other traditional types of song was in decline, and Coates's output dropped accordingly. The violist and music scholar Michael Ponder writes that Coates, who was principally interested in writing orchestral music, found writing songs limiting and did so chiefly to fulfil his contract with his publisher.[19] Nevertheless, Ponder considers that some of Coates's later songs show him at his finest. He praises "Because I miss you so" and "The Young Lover" (both 1930) for their "rich, glorious melodic vocal line" supported by "subtle piano writing that maintains the unity and intensifies the colour and effect of the vocal line". Almost all the songs, whether from the composer's early, middle or late periods, are in a slow or fairly slow tempo. Ponder comments that Coates's last songs were on a grander scale, perhaps influenced by the big numbers in West End and Broadway shows.[19]

Coates chose texts by a wide range of authors, including Shakespeare, Christina Rossetti, Arthur Conan Doyle; among those whose words he set most often were Weatherly, Phyllis Black (Mrs Coates), and Royden Barrie.[n 5] On one occasion he wrote his own words: "A Bird's Lullaby" (1911).[53]

Other music

[edit]Coates always conceived his music in orchestral terms, even when writing for solo voice and piano. Despite his background as a member of three string quartets, he composed little chamber music. Grove lists five such works by Coates, three of which are lost. The two surviving pieces are a minuet for string quartet from 1908, and "First Meeting" (1941) for viola and piano.[24] Similarly, although he learned a substantial part of his craft while playing in theatre orchestras, Coates wrote no musical shows. When he toured with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducting his own music, in 1940, the reviewer in The Manchester Guardian urged him to find a librettist and write a comic opera: "He ought to succeed greatly in that line. He is quick-witted, has a gift for lilting melody, deals in spicy and exhilarating harmony, and scores his music with a brilliancy that tells of experienced craftsmanship".[54] Coates did not follow the paper's advice. His biographer Geoffrey Self suggests that he simply lacked the stamina, the aggressiveness or possibly the inclination to write for the musical theatre.[55]

The few ventures Coates made into drama were for the cinema rather than the theatre. His orchestral phantasy Cinderella was first heard in the film A Symphony in Two Flats, and he contributed the "Eighth Army March" to the 1941 war film Nine Men and the "High Flight March" to High Flight (1957).[56] As noted above, his most celebrated piece of cinema music, "The Dam Busters March", was not written specially for the film. With these exceptions, Coates declined the offers from producers in Britain and the US who continually sought to secure his services. He realised that film music is liable to be cut, rearranged, or otherwise changed to meet the requirements of directors, and, mindful of such difficulties encountered by Arthur Bliss in composing the score for Things to Come, he did not wish his music to be subjected to similar treatment.[57][58]

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Coates's parents originally intended to christen him "Francis Harrison", and changed their minds to add the first name. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article (2001) is headed "Coates, Eric [formerly Frank Harrison Coates]"; a later biography, by Michael Payne (2012) records that Coates's birth certificate contains all three given names.[1]

- ^ The obituaries of Coates in The Times, The Manchester Guardian and The Musical Times give the year as 1918,[17][22][23] but later sources including Grove, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Coates's biographer Michael Payne, and Coates in his memoirs, give the year as 1919.[3][24][25]

- ^ The lyric was written by Jack Lawrence.[35]

- ^ Another reviewer wrote in the same year: "The Dam Busters March is undeniably a masterpiece of British light music flying high and proud. It is sung on football terraces, particularly when England plays Germany. It echoes repeatedly through One of My Turns, a song on Pink Floyd's The Wall album. It can be heard, reiterated, during the climax of George Lucas's Star Wars. It is at once rousing and as cosy as an old labrador."[40]

- ^ Barrie was a pen name used by Rodney Bennett (1890–1948), father of the composer Richard Rodney Bennett.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Payne, p. 11

- ^ Payne, p. 9

- ^ a b c d e f g Self, Geoffrey. "Coates, Eric (formerly Frank Harrison Coates)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Pratt and Grove, p. 246; Jones, Keith and Gordon Goldsborough "Ralph Joseph Horner (1848-1926)", Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 27 September 2018; and Rollins and Witts, p. 30

- ^ Coates, pp. 39–40

- ^ McDonald, p. 3

- ^ Bratby, Richard (2019) Notes to Chandos CD 20036

- ^ Payne, pp. 17–18 and 19–20

- ^ "Concerts", The Times, 13 December 1907, p. 12

- ^ "Royal Academy of Music", The Times, 16 December 1908, p. 11

- ^ "Royal Academy of Music", The Musical Times, Vol. 49, No. 779 (9 January 1908), p. 31 (subscription required)

- ^ "Obituary: William Primrose", The New York Times, 4 May 1982, p. 31

- ^ Forbes, Watson. "Tertis, Lionel", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ White, p. 145

- ^ McDonald, p. 5; and Rollins and Witts, p. 21

- ^ McDonald, p. 6

- ^ a b c "Mr Eric Coates", The Times, 23 December 1957, p. 8

- ^ "Music", The Times, 17 September 1909, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Ponder, Michael (1995). Notes to Naxos CD 8.223806

- ^ a b "Eric Coates", Boosey and Hawkes. Retrieved 29 September 2018

- ^ "The Theatres", The Times, 21 September 1922, p. 8

- ^ a b c "Eric Coates", The Manchester Guardian, 23 December 1957, p. 8

- ^ a b "Eric Coates", The Musical Times, 99, no. 1380 (1958), p. 99

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Self, Geoffrey. "Coates, Eric", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ Payne, p. 52; and Coates, p. 75

- ^ Coates, p. 194; and McDonald, p. 10

- ^ "Summer Days", BBC Proms performance archive. Retrieved 29 September 2018

- ^ "Prom 43, 30 Sep 1922 Queen's Hall" and "Prom 47, 7 Oct 1926 Queen's Hall", BBC Proms performance archive. Retrieved 29 September 2018

- ^ Kay, Brian (2002). Notes to Chandos CD 9869 OCLC 754451222

- ^ Payne, pp. 46 and 56

- ^ a b c "Coates, Eric", Dictionary of National Biography archive, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 September 2018. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ McDonald, p. 12

- ^ McDonald, pp. 13 and 20

- ^ Payne, p. 110

- ^ Payne, p. 241

- ^ Payne, p. 159; and "Desert Island Discs", BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2018

- ^ McDonald, p. 16

- ^ Payne, p. 17

- ^ Jeffries, Stuart. "Listen with prejudice", The Guardian, 31 January 2003, p. B14

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan."Bombs away", The Guardian, 6 May 2003, p. A6

- ^ Payne, p. 218

- ^ "Funeral: Mr. Eric Coates", The Times, 27 December 1957, p. 8

- ^ Self, p. 87

- ^ Payne, p. 80

- ^ Payne, p. 72

- ^ Payne, p. 37

- ^ Coates, p. vii

- ^ Payne, p. xv

- ^ Eric Coates: Orchestral Works Volume 2, reviewed at MusicWeb International

- ^ McDonald, p. 15

- ^ Lace, Ian. "John Wilson – Conductor, Arranger, and Eric Coates Archivist", Fanfare Vol. 21, Issue. 6, (July 1998), pp. 44-49

- ^ Meredith and Harris, fifth page of Chapter 2 in Kindle edition

- ^ Payne, p. 233

- ^ "Palace Theatre", The Manchester Guardian, 20 November 1940, p. 6

- ^ Banfield, Stephen. "Coates of Many Colours", The Musical Times, Vol. 129, No. 1745 (July 1988), p. 348 (subscription required)

- ^ "Eric Coates", British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 September 2018

- ^ McDonald, p. 28

- ^ Self, p. 93

Sources

[edit]- Coates, Eric (1986) [1953]. Suite in Four Movements: An Autobiography. London: Thames. ISBN 978-0-905210-38-4.

- McDonald, Tim (1993). Eric Coates: Notes to CD 8.223455. Hong Kong: Marco Polo. OCLC 761492527.

- Meredith, Anthony; Paul Harris (2010). Richard Rodney Bennett: The Complete Musician. London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-0-85712-588-0.

- Payne, Michael (2016). Life and Music of Eric Coates. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-27149-4.

- Pratt, Waldo Selden; George Grove (1920). American Music and Musicians. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 86049167.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419.

- Self, Geoffrey (1986). In Town Tonight: A Centenary Study of Eric Coates. London: Thames. ISBN 978-0-905210-37-7.

- White, John (2012) [2006]. Lionel Tertis: The First Great Virtuoso of the Viola. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-84383-790-9.

External links

[edit]- Eric Coates at IMDb

- Eric Coates at AllMusic

- Eric Coates discography at Discogs

- Eric Coates discography at MusicBrainz

- Biography at the Robert Farnon Society

- Free scores by Eric Coates at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- 1886 births

- 1957 deaths

- 20th-century British classical composers

- 20th-century English composers

- 20th-century English male musicians

- 20th-century violists

- Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music

- English classical violists

- English film score composers

- English light music composers

- English male film score composers

- Golders Green Crematorium

- People from Hucknall